CTF Writeup - HTB Cyber Apocalypse 2025

Prologue

These are my writeups of a few of the reverse engineering problems I tackled during this year’s HacktheBox Cyber Apocalypse 2025 CTF. Unfortunately, I could only allocate a few hours in the evenings to engaging the problems and wasn’t able to finish the complete set.

I found myself reaching for GDB and Ghidra for almost all of the problems vs. approaching them with more programmatic/automated solutions. Towards the end of my participation, I found one problem (SingleStep - did not finish) to be particularly vexxing since it was a self-modifying binary that unspooled as it executed, rendering static analysis pretty moot. I found myself thinking back on one of my college classes for malware analysis and thought it might be worthwhile to perform some concolic analysis with angr, but ran out of time. As an after-action, that’s something I’ll want to brush-up on for future challenges.

Anyhow, on with the writeup!

Reversing

SealedRune

There was probably an easier way to go about this than I did, but to each their own!

I started by popping the binary into Ghidra, which mapped out the binary’s functions.

For the unfamiliar: Ghidra is freely-available suite of reverse engineering and binary analysis tools published/maintained by the NSA. Among its other features, it includes a disassembler and a decompiler (the latter offering a best guess at rebuilding the source code in C). Throughout this writeup, I’ve copied the decompiled source code provided by Ghidra into the post.

Thankfully, there were plenty of symbols in place that let us get quickly oriented to the binary’s functionality. This can be inferred by running the file <filename> command on the binary and observing that those symbols were not stripped. By having those symbols retained at compiled-time, Ghidra’s decompiler is able to rebuild things like the original method names.

main()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

undefined8 main(void)

{

long in_FS_OFFSET;

undefined local_48 [56];

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

anti_debug();

display_rune();

puts(&DAT_00102750);

printf("Enter the incantation to reveal its secret: ");

__isoc99_scanf(&DAT_001027c5,local_48);

check_input(local_48);

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}

Looking at the above, we can see:

- The binary would start by calling

anti_debug(), which would terminate the program if it detected it was in a debugger, likeGDB. This is meant to stymie dynamic analysis. - The binary would do some graphical output before prompting the user for input, passing that input to

check_input().

check_input()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

void check_input(char *param_1)

{

int iVar1;

char *__s2;

long lVar2;

__s2 = (char *)decode_secret();

iVar1 = strcmp(param_1,__s2);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

puts(&DAT_00102050);

lVar2 = decode_flag();

printf("\x1b[1;33m%s\x1b[0m\n",lVar2 + 1);

}

else {

puts("\x1b[1;31mThe rune rejects your words... Try again.\x1b[0m");

}

free(__s2);

return;

}

check_input()would decode the stored secret, compare it to what we entered and then decode the flag if it matched withdecode_flag()

decode_flag()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

undefined8 decode_flag(void)

{

undefined8 uVar1;

uVar1 = base64_decode(flag);

reverse_str(uVar1);

return uVar1;

}

- Decode flag would load the flag from memory, then base64-decode it and reverse the string.

There’s several ways we could have gone about this, but I ended up reaching for GDB.

GDB has a lot of neat tricks to it, including being able to arbitrarily jump to any valid instruction we want (e.g. jump *0x555555555462); bear in mind, GDB resumes process execution after the jump, so we also want to set breakpoints (b) to pause and observe state. Doing this lets us trivially skip over anti_debug() (and - in fact - go wherever we want). With that we could jump to where decode_secret() is invoked in check_input() (and thereby learn the secret we need to pass):

VaelGnuffraz

Or we could jump into decode_flag() directly and grab the base64-encoded string:

LmB9ZDNsNDN2M3JfYzFnNG1fM251cntCVEhgIHNpIGxsZXBzIHRlcmNlcyBlaFQ=

Or even the decoded flag:

The secret spell is HTB{run3_m4g1c_r3v34l3d}.

EncryptedScroll

Like before, we can load this binary into Ghidra to get a sense of how this binary behaves.

main()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

undefined8 main(void)

{

long in_FS_OFFSET;

undefined local_48 [56];

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

anti_debug();

display_scroll();

printf(&DAT_00102220);

__isoc99_scanf(&DAT_00102268,local_48);

decrypt_message(local_48);

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}

This challenge behaves similarly to the last insofar as having an anti_debug() method, some ASCII art, and then a call to decrypt_message() to invariably get a flag.

decrypt_message()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

void decrypt_message(char *param_1)

{

int iVar1;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

int local_3c;

undefined8 local_38;

undefined4 local_30;

undefined4 uStack_2c;

undefined4 uStack_28;

undefined8 local_24;

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

local_38 = 0x716e32747c435549;

local_30 = 0x6760346d;

uStack_2c = 0x6068356d;

uStack_28 = 0x75327335;

local_24 = 0x7e643275346e69;

for (local_3c = 0; *(char *)((long)&local_38 + (long)local_3c) != '\0'; local_3c = local_3c + 1) {

*(char *)((long)&local_38 + (long)local_3c) = *(char *)((long)&local_38 + (long)local_3c) + -1;

}

iVar1 = strcmp(param_1,(char *)&local_38);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

puts("The Dragon\'s Heart is hidden beneath the Eternal Flame in Eldoria.");

}

else {

puts("The scroll remains unreadable... Try again.");

}

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return;

}

We can see that a number of operations are performed on some bytes, ultimately comparing user input to the flag. Ergo, the trivial solution is to jump to the cmp instruction (where the strcmp() call is made above), which would show us the flag that’s getting compared against:

HTB{s1mpl3_fl4g_4r1thm3t1c}

EndlessCycle

This binary - unlike SealedRune - didn’t come with all the symbols necessary to neatly rebuild main and its relative components. However, we could still dump strings from the binary and then search for those strings getting called in the binary’s assembly with Ghidra. In fact, if we ran the binary straightaway, we could also get a rough estimation of where our input landed within.

FUN_00101169()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

undefined8 FUN_00101169(void)

{

int iVar1;

code *pcVar2;

ulong local_28;

ulong local_20;

pcVar2 = (code *)mmap((void *)0x0,0x9e,7,0x21,-1,0);

srand(DAT_001042b8);

for (local_28 = 0; local_28 < 0x9e; local_28 = local_28 + 1) {

for (local_20 = 0; local_20 < (ulong)(long)*(int *)(&DAT_00104040 + local_28 * 4);

local_20 = local_20 + 1) {

rand();

}

iVar1 = rand();

pcVar2[local_28] = SUB41(iVar1,0);

}

iVar1 = (*pcVar2)();

if (iVar1 == 1) {

puts("You catch a brief glimpse of the Dragon\'s Heart - the truth has been revealed to you");

}

else {

puts("The mysteries of the universe remain closed to you...");

}

return 0;

}

This is - presumably - main(), if not a function that gets called within main().

Something that was a little interesting from the get-go is that we see the string What is the flag? printed directly to the console when we run the binary, but we can’t find that string in our binary through Ghidra.

It turns out, the reason for this is owed to the above nested for-loop, terminating with the iVar1 assignment to (*pcVar2)(). In effect this is creating some shellcode to execute, which is responsible for ingesting and handling our user input.

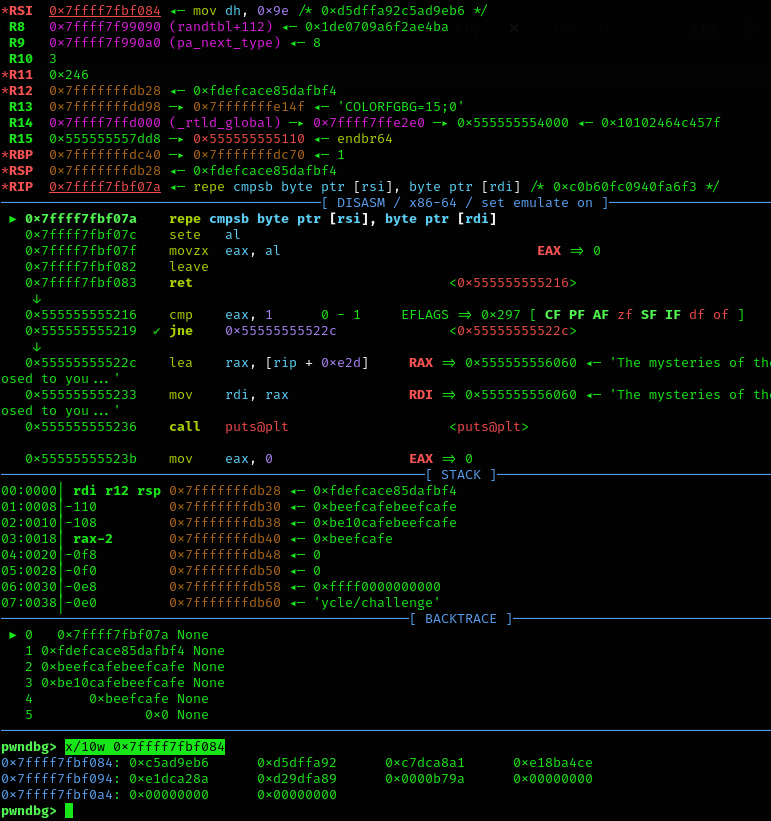

At first, I tried dumping the contents of rax at the call rax instruction right where (*pcVar2)() invokes, and then disassemble them with https://defuse.ca/online-x86-assembler.htm#disassembly2. However, this proved inaccurate. Instead, it proved easier to simply use GDB’s step (s) function to step into the function call. After that, we could dump the instructions for a more accurate picture:

x/50i $pc

0x7ffff7fbf000: push rbp

0x7ffff7fbf001: mov rbp,rsp

0x7ffff7fbf004: push 0x101213e

0x7ffff7fbf009: xor DWORD PTR [rsp],0x1010101

0x7ffff7fbf010: movabs rax,0x67616c6620656874

0x7ffff7fbf01a: push rax

0x7ffff7fbf01b: movabs rax,0x2073692074616857

0x7ffff7fbf025: push rax

0x7ffff7fbf026: push 0x1

0x7ffff7fbf028: pop rax

0x7ffff7fbf029: push 0x1

0x7ffff7fbf02b: pop rdi

0x7ffff7fbf02c: push 0x12

0x7ffff7fbf02e: pop rdx

0x7ffff7fbf02f: mov rsi,rsp

0x7ffff7fbf032: syscall

0x7ffff7fbf034: sub rsp,0x100

0x7ffff7fbf03b: mov r12,rsp

0x7ffff7fbf03e: xor eax,eax

0x7ffff7fbf040: xor edi,edi

0x7ffff7fbf042: xor edx,edx

0x7ffff7fbf044: mov dh,0x1

0x7ffff7fbf046: mov rsi,r12

0x7ffff7fbf049: syscall

0x7ffff7fbf04b: test rax,rax

0x7ffff7fbf04e: jle 0x7ffff7fbf082

0x7ffff7fbf050: push 0x1a

0x7ffff7fbf052: pop rax

0x7ffff7fbf053: mov rcx,r12

0x7ffff7fbf056: add rax,rcx

0x7ffff7fbf059: xor DWORD PTR [rcx],0xbeefcafe

0x7ffff7fbf05f: add rcx,0x4

0x7ffff7fbf063: cmp rcx,rax

0x7ffff7fbf066: jb 0x7ffff7fbf059

0x7ffff7fbf068: mov rdi,r12

0x7ffff7fbf06b: lea rsi,[rip+0x12] # 0x7ffff7fbf084

0x7ffff7fbf072: mov rcx,0x1a

0x7ffff7fbf079: cld

0x7ffff7fbf07a: repz cmps BYTE PTR ds:[rsi],BYTE PTR es:[rdi]

0x7ffff7fbf07c: sete al

0x7ffff7fbf07f: movzx eax,al

0x7ffff7fbf082: leave

0x7ffff7fbf083: ret

0x7ffff7fbf084: mov dh,0x9e

0x7ffff7fbf086: lods eax,DWORD PTR ds:[rsi]

0x7ffff7fbf087: (bad)

0x7ffff7fbf08a: (bad)

0x7ffff7fbf08c: movabs eax,ds:0x8ae18ba4cec7dca8

0x7ffff7fbf095: movabs ds:0xb79ad29dfa89e1dc,al

At a high-level, the assembly instructions are writing out the prompt “What is the flag?”, then reading in input to the buffer. It then reads in the user’s input, the XORs the bytes of that input - 4 bytes at a time - against the key 0xbeefcafe. Finally, it compares the XOR’d output against the XOR’d flag at 0x7ffff7fbf07a; assuming the bytes match, then the shellcode returns 1 (otherwise it returns 0).

By setting a breakpoint at 0x7ffff7fbf07a, we can dump the XOR’d bytes of the flag…

1

2

0xc5ad9eb6 0xd5dffa92 0xc7dca8a1 0xe18ba4ce

0xe1dca28a 0xd29dfa89 0x0000b79a

…and XOR each set of 4 bytes again against 0xbeefcafe (as XORing bytes twice against the same key returns the same result). Converting the re-XOR’d bytes to ASCII gives the flag:

HTB{l00k_b3y0nd_th3_w0rld}

ImpossiMaze

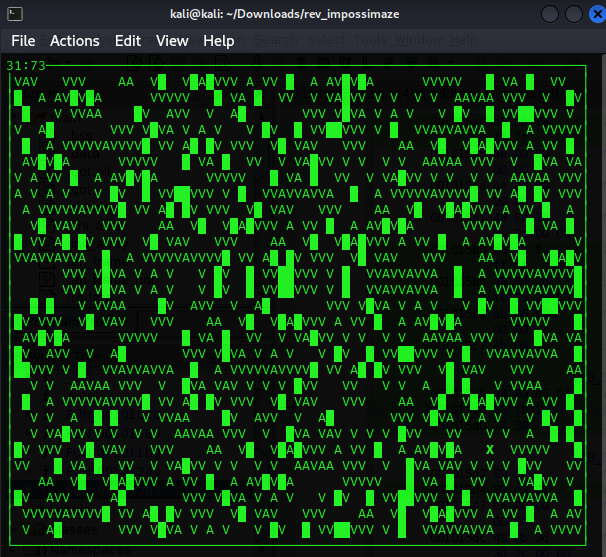

This binary put out a seemingly random grid, with a player-controlled “X” to navigate about using the arrow keys.

This was the first problem in the CTF that it wasn’t immediately apparent to me where the flag was meant to be produced. I thought at the onset that we were meant to debug the functionality of the game, then play it somehow in a particular way as to revealing the flag. That didn’t end up being the case.

There were a few custom functions defined, but only one that Ghidra really produced anything notable for us to review.

FUN_00101283

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

undefined8 FUN_00101283(void)

{

int iVar1;

uint uVar2;

uint uVar3;

uint uVar4;

ulong uVar5;

char cVar6;

int iVar7;

int *piVar8;

int iVar9;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

int local_68;

int local_64;

char local_58 [24];

long local_40;

local_40 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

initscr();

cbreak();

noecho();

curs_set(0);

keypad(stdscr,1);

local_64 = getmaxy(stdscr);

uVar5 = getmaxx(stdscr);

local_68 = (int)(((uint)(uVar5 >> 0x1f) & 1) + (int)uVar5) >> 1;

local_64 = local_64 / 2;

iVar9 = 0;

do {

uVar3 = getmaxy(stdscr);

uVar4 = getmaxx(stdscr);

if (iVar9 == 0x104) {

local_68 = local_68 - (uint)(1 < local_68);

}

else if (iVar9 < 0x105) {

if (iVar9 == 0x102) {

local_64 = local_64 + 1;

}

else if (iVar9 == 0x103) {

local_64 = local_64 - (uint)(1 < local_64);

}

}

else {

local_68 = local_68 + (uint)(iVar9 == 0x105);

}

werase(stdscr);

wattr_on(stdscr,0x100000,0);

wborder(stdscr,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0);

if (2 < (int)uVar4) {

iVar9 = 1;

do {

iVar7 = 1;

if (2 < (int)uVar3) {

do {

uVar2 = FUN_00101249(iVar9,iVar7);

if ((int)uVar2 < 0x3d) {

cVar6 = 'A';

if ((int)uVar2 < 0x1f) {

cVar6 = (-(uVar2 < 0x1f) & 0x85U) + 0x56;

}

}

else {

cVar6 = (-(uVar2 - 0x3d < 0x78) & 0xcaU) + 0x56;

}

iVar1 = wmove(stdscr,iVar7,iVar9);

if (iVar1 != -1) {

waddch(stdscr,(int)cVar6);

}

iVar7 = iVar7 + 1;

} while (iVar7 != uVar3 - 1);

}

iVar9 = iVar9 + 1;

} while (uVar4 - 1 != iVar9);

}

wattr_off(stdscr,0x100000,0);

wattr_on(stdscr,0x200000,0);

iVar9 = wmove(stdscr,local_64,local_68);

if (iVar9 != -1) {

waddch(stdscr,0x58);

}

wattr_off(stdscr,0x200000,0);

snprintf(local_58,0x10,"%d:%d",(ulong)uVar3,(ulong)uVar4);

iVar9 = wmove(stdscr,0,0);

if (iVar9 != -1) {

waddnstr(stdscr,local_58,0xffffffff);

}

if ((uVar3 == 0xd) && (uVar4 == 0x25)) {

wattr_on(stdscr,0x80000,0);

wattr_on(stdscr,0x200000,0);

piVar8 = &DAT_001040c0;

iVar9 = 6;

do {

iVar7 = iVar9 + 1;

iVar9 = wmove(stdscr,6,iVar9);

if (iVar9 != -1) {

waddch(stdscr,(&DAT_00104120)[*piVar8]);

}

piVar8 = piVar8 + 1;

iVar9 = iVar7;

} while (iVar7 != 0x1e);

wattr_off(stdscr,0x200000,0);

wattr_off(stdscr,0x80000,0);

}

iVar9 = wgetch(stdscr);

} while (iVar9 != 0x71);

endwin();

if (local_40 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}

The above code defines the process’ main game-loop. A lot about this may be pretty overwhelming (and ultimately - not of consequence to solving this), but there’s something in particular our attention can be brought to:

1

if ((uVar3 == 0xd) && (uVar4 == 0x25))

The above if-check looks at uVar3 and uVar4, which we can see in the code reference the rows/columns of the terminal that’s running the game board. If they equate to 0xd and 0x25 (13 and 37, respectively), the game board renders a hidden message, namely:

HTB{th3_curs3_is_brok3n}